A few weeks ago, a colleague, said, “You know, after someone dies, that person will remain alive as long as there is someone to say their name.”

February is Black History Month. It is the month when African Americans celebrate their ancestors’ legacy. On Tuesday February 3, beginning at 7:00 pm, I will call out my ancestor, my Grandfather, Joseph B. Stratton, who served with the Union Navy from 1863-1864 in the Civil War.

Through the wonders of Zoom, I am honored to sit inside the Bucks County Civil War Museum and Library of Doylestown to present a Power Point lecture about my Grandfather. From the comfort of your home, you will learn about one Black man’s experience that happened during a significant chapter in our Nation’s 250 years of Democracy.

Please register for this free event at this email: civilwarmuseumdoylestown@gmail.com. Join family, friends, and history buffs while I share my Grandfather’s legacy who during the Civil War, served on a blockade runner along the Eastern shore from Wilmington, Delaware to South Carolina. Equally, it is exciting for me because I will present this Zoom from the Doylestown Civil War Museum and Library, where I will be surrounded by their collection of artifacts and documents.

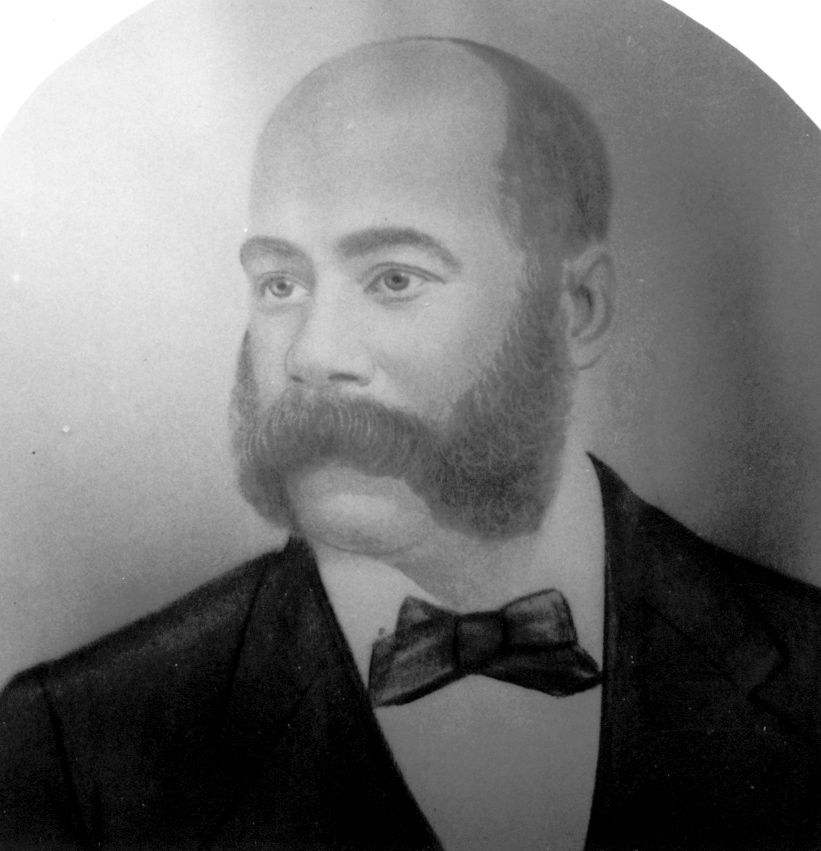

The picture with this narrative is the only image of my Grandfather. However, through the wonders of Ancestry.com, we have traced our Stratton surname to Tobias Stratton, my Great-Great Grandfather, born a Free Black in 1767 Philadelphia.

Tobias married Harriet Mintas in 1795, a Jamaican woman. Our Stratton legacy had begun. We know little about my Great-Great Grandfather’s life in Philadelphia. I imagine him walking the cobblestones of the city. Did he see Benjamin Franklin at his printing press? And at age 9, did he push his way through a joyful crowd for a better position to witness the reading of the Declaration of Independence for the first time?

Who, I wonder, were my ancestors before Tobias?

The first Africans arrived on the shores of Virginia in 1619. For two hundred years, enslavement created a gap of procreated amnesia. My DNA chart from Ancestry.com discovered 45% of four different north European countries and the rest? Ten different countries from Africa, my Motherland.

Gaps.

Currently there is an intolerant crusade, determined to erase Black existence, it is rumbling across America, determined to forbid the culture, contributions, and history of ancestors such as mine: Joseph B. Stratton—a Black man of America: a son, a husband, and a father; he was an educated man, a barber, an activist, a veteran of the Union Navy, and a patriot. He was my Grandfather.