My February 9 post, Preservation Zero. Progress One featured Addison Hutton, the architect who designed the 19th Century Bucks County Court House. On February 17, Grafitti on East Court Street promised to write about the protesters who painted THE SINS COMMITTED IN THE NAME OF PROGRESS on the construction fence surrounding the demolition site of the old Court House. With a large can of black paint and some brushes, three teenagers plastered the message on the entire length of the fence along E. Court Street, from Broad Street down to the intersection where the streets of Main, Shewell and Court finger away in different directions.

My February 9 post, Preservation Zero. Progress One featured Addison Hutton, the architect who designed the 19th Century Bucks County Court House. On February 17, Grafitti on East Court Street promised to write about the protesters who painted THE SINS COMMITTED IN THE NAME OF PROGRESS on the construction fence surrounding the demolition site of the old Court House. With a large can of black paint and some brushes, three teenagers plastered the message on the entire length of the fence along E. Court Street, from Broad Street down to the intersection where the streets of Main, Shewell and Court finger away in different directions.

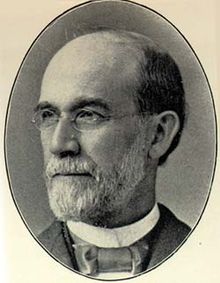

The image above appeared in my February 17 post.

Somewhere there is a photograph that was taken within days after “THE SINS …” graffiti was discovered on the fence. It possibly was published in The Doylestown Intelligencer (now called The Intelligencer), according to a persistent researcher at the Doylestown Historical Society who found a third or fourth generation image in the Spruance Library’s microfiche collection.The photographer must have snapped the picture from the second or third floor of the old Doylestown Boro School which was located catty-corner at Broad & Court Streets. The words are invisible in that image. After inquiries to other historians, former and current publications, and a post on the ‘Growing Up In Doylestown’ facebook page, I came up empty in my search for that photograph.

Over 50 years ago the buildings across the street on East Court Street that face the Court House were homes to Doylestown families. If you walked on the pavement after 10 on any given evening it was typical to find no lights at all shining from the windows of those homes. And as you walked not one human being would cross your path. Now the homes are attorney offices. On this particular July 1958 night, three teenagers decided to make a statement about the loss of the nearly century old County Court House that was being demolished to make way for a more “modern” building.

I spoke to two of the three artists: Ed Greiner and Anne McHugh. Anne who lives in New Jersey apologized for not trusting her memory about this incident that happened 57 years ago. She did however get me in touch with Ed who now makes his home in Maine. The three of them were able to accomplish their task on a dark July night in 1958. Their only fear had been the prospect of getting caught by their “arch enemy” – Doylestown Police Officer George Silk. Officer Silk often stopped young people who were walking around town after dark; so this midnight excursion was a bold move by the three of them. Not anywhere close to being “juvenile delinquents”, if caught the prank might have been considered Destruction of property or Vandalism.

They hurriedly slapped the words “THE SINS COMMITTED IN THE NAME OF PROGRESS” across the fence along E. Court Street. In a letter to this blog, Ed confessed, “I did drop an ‘M’ or else a ‘T’ from committed, but I was never a strong speller. I made up the statement (maybe). We probably may have had a getaway car and driver.” Ed gets his activism from his mother, Martha Darlington, best described by Ed as a “preservationist”. He recalled how she was a faithful attendee at the County Commissioners’ meetings where she expressed her opposition of losing this iconic structure to the wrecking ball. Each time she spoke during public comments, Ed said “… she was steamrolled”. His mother was one of those Doylestown citizens who pitched in around town when something needed to be done. “Once”, Ed told me, “She gathered some people to go into the woods surrounding Font Hill to clear away underbrush. “She even recruited a Boy Scout troop to help.”

Ed also recalled how back in the day the expanse of lawn surrounding the Court House was a venue for band concerts. At that time there was only one memorial on the lawn, a World War I fountain with two soldiers–one cradling a wounded soldier. After the new court house was built the fountain was relocated to the corner of North Main and Broad Streets. The lawn is now a place with memorials to five wars and a sixth to fireman killed in the line of duty.

Within days after its appearance, local residents would stand in front of the fence, arms crossed in front of them as they silently stared at the message. Before a week had gone by the message was covered over with dark green paint. I smiled every time I walked past the fence because looking closely, the three protestors’ message was still visible. It was a half-ass attempt to suppress a statement that in the 21st Century could be painted on demolition fences surrounding old treasured buildings or land speculators bulldozing farmland.

Elizabeth Biddle Yarnall, the niece of Addison Hutton, described her uncle in her biography of him as a “Nonconforming Quaker”. Addison would be pleased that almost a hundred years later, three teenagers admired his vision enough to pay homage to him with a classic graffiti statement.